January 2024 human genetics roundup

A brief look at the most exciting stories from Jan, 2024

Happy February! It feels like the year 2024 has just started but we are already in the second month of this year. As I mentioned before, this year I wanted to write more in Substack. Here I review some of the interesting papers that I read last month. The goal is to do this every month or at least, once every two months. But I am not sure if I’ll manage to do that. We’ll see as the time flies. For now, enjoy these stories, some of which I am sure you’ll find quite fascinating. Note, I saved the best for last. Don’t miss that!

Noncoding genome

A part of the human genome that will never cease to intrigue scientists is the noncoding genome. No matter how many discoveries of noncoding mutations causing human diseases have already been made, new ones will always bring interesting twists and turns to our understanding of the noncoding universe and will remind us again and again that we are still only scratching the surface. So, you can guess why whenever I write a roundup, there is always a section on the noncoding genome.

A paper published last month in Nature describes a surprising mechanism through which transcription factors (TFs) interact with enhancers to control tissue-specific gene expression.

If asked to guess how a TF binding to an enhancer region results in a tissue-specific expression of a gene, we’d probably imagine that the TF binds with the enhancer with a high affinity and any mutations that misspell the enhancer sequence would result in the TF failing to bind with the enhancer resulting in aberrant gene expression and disease. The paper by Emma Farley and colleagues from the University of California tells the opposite story.

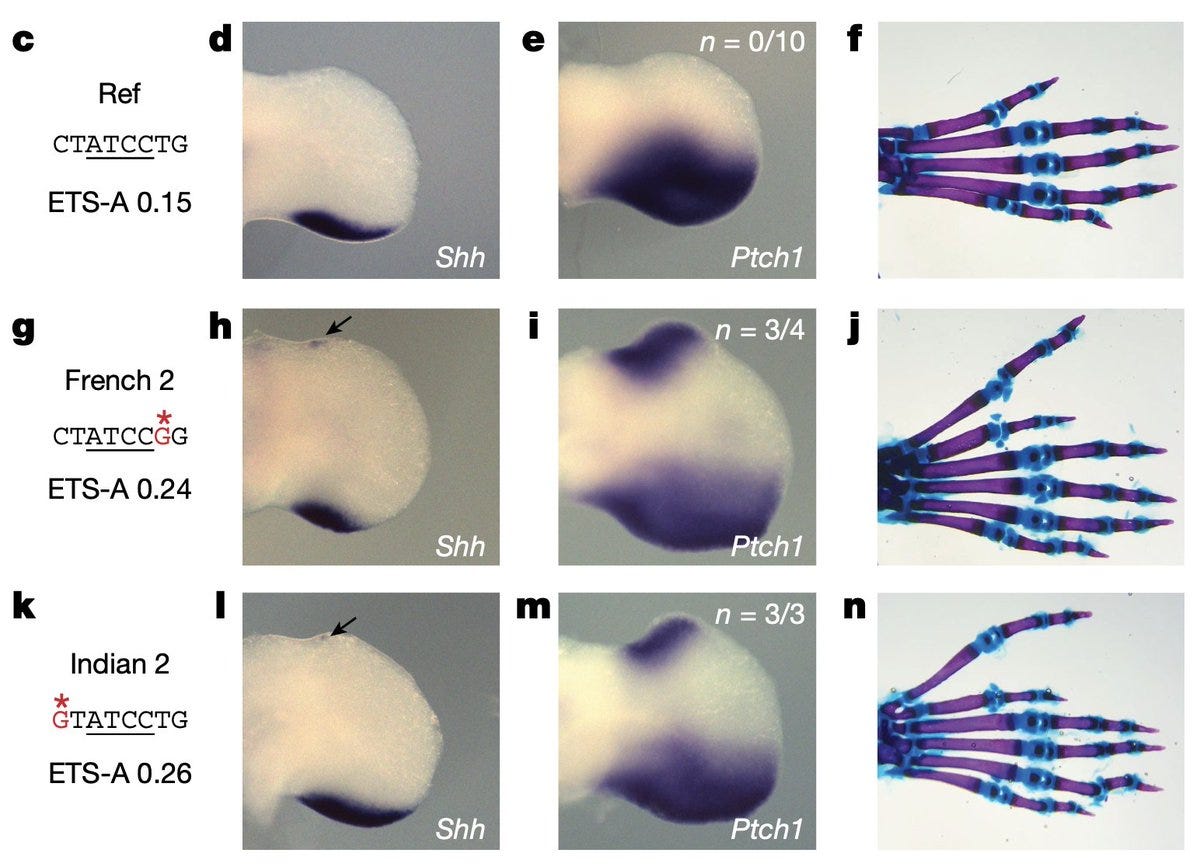

Probing the mechanisms underlying noncoding mutations causing polydactyly in humans and mice, the authors uncovered a surprising enhancer mechanism. It seems an enhancer called ZRS, which is frequently disrupted by the polydactyly mutations, maintains the tissue specificity of its target genes by keeping its binding affinity with transcription factors not high but surprisingly low. The transient and subtle interaction of the TFs with the ZRS is what causes its target gene SHH to express within the correct boundaries of the developing limb. Any over-affection between TFs and ZRS (caused by mutations) causes spillage of SHH expression resulting in the development of extra fingers.

More interestingly, the low-affinity TF binding sites are distributed over multiple redundant units within the ZRS enhancer thereby loss of one is buffered by the others—a foolproof evolutionary mechanism to guard against harmful loss of function mutations. But the master design came with a loophole: vulnerability towards gain of function mutations. Perhaps, bearing a few extra fingers is a small price to pay to avoid losing the limb altogether.

The most fascinating part is that this mechanism is also observed in invertebrates, for example, in sea squirts, analogous enhancer mutations have been found to result in developmental anomalies, sometimes as severe as having two beating hearts. So, it appears that this noncoding mechanism is very ancient and may have been perfected over millions of years of evolution.

GxE and GxG interactions

Since the dawn of human genetics, scientists have always been fascinated by gene-environment (GxE) and gene-gene (GxG) interactions. If you flip through the pages of human genetics literature, particularly the ones from the pre-GWAS era, you’ll find thousands of candidate gene studies on GxG and GxE interactions. GxG and GxE interaction studies require sample sizes much larger than what is required for a simple genetic association study. The findings from most of the candidate gene association studies from the pre-GWAS era themselves turned out later to be false positives. I’ll let you guess how the candidate gene GxG and GxE studies might have panned out.

To identify an interaction effect of a variant with an environment or with another variant, two things are required.

The variant’s frequency in the population is common enough that when you stratify the population based on the variant genotypes, you get decent sample sizes in each group.

The effect size of the variant’s association with the phenotype is large enough that the characteristics of the genotype groups are sufficiently different to enable the discovery of genetic or environmental differences between them.

To date, only a few variants in the human genomes have been found that tick both of the boxes above, most of which have been identified either long before the GWAS era (from family-based linkage studies followed by cloning or targeted sequencing, e.g., APOE association with Alzheimer’s, ALDH2 & alcohol behaviour in East Asians etc.) or during the early GWAS era when scientists were harvesting the low-hanging discoveries: CFH associated with AMD, PNPLA3 & fatty liver, CHRNA5 & smoking, APOL1 & chronic kidney disease in Africans and African Americans, and so on.

There are many flavours of GxE interactions.

In one, a gene interacts with an environment and influences the outcome. Here. the gene acts exclusively through the environment and without the environment, the gene does not affect the phenotype. An example of this type of GxE interaction is CHRNA5 interacting with smoking to increase the risk of lung cancer. CHRNA5 encodes a nicotine acetylcholine receptor expressed in the brain and individuals who carry a common missense variant that decreases the CHRNA5 activity in the brain are at increased risk of smoking heavily and in turn, are at increased risk of developing lung cancer.

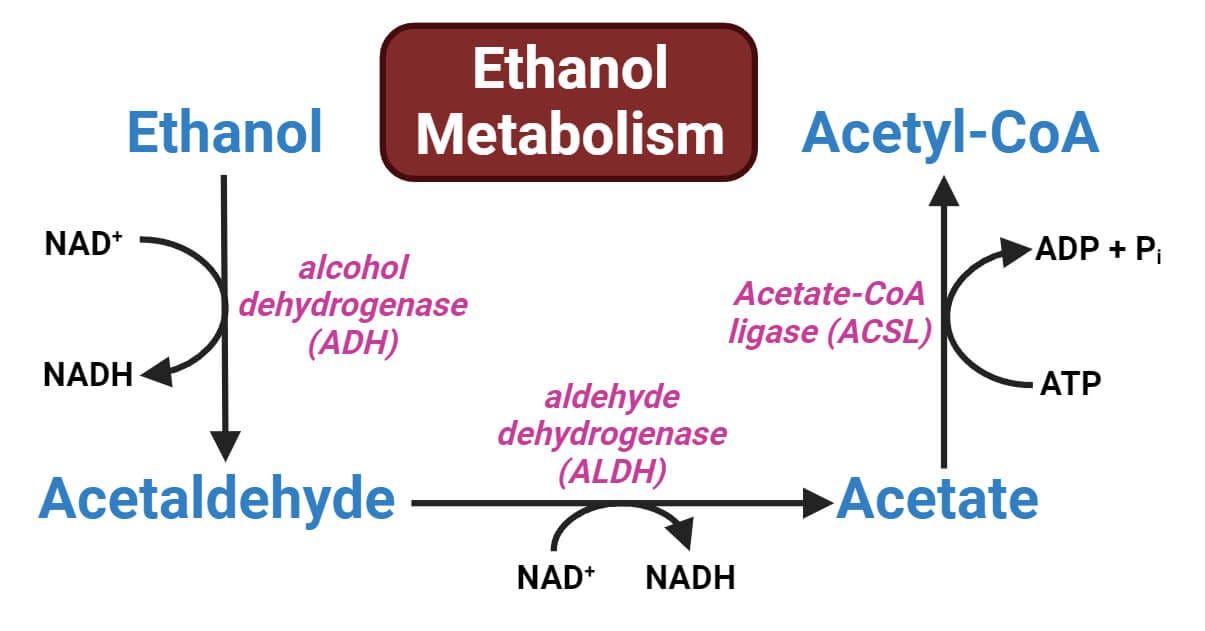

In another, the environment interacts with a gene to influence the outcome. Here, the environment acts exclusively through a gene, and in the absence of the gene (that is, the genetic variant in the gene), the environment has no association with the phenotype. An example of this type of GxE is alcohol drinking interacting with ALDH2 to increase the risk of oesophageal cancer. ALDH2 encodes acetaldehyde dehydrogenase that clears the acetaldehyde, a toxic and carcinogenic intermediate of alcohol metabolism, and individuals from East Asia carrying a common inactivating missense variant in ALDH2 who drink alcohol are at higher risk of oesophageal cancer.

The word “interaction” in its strictest sense refers to the second GxE scenario in which either the G or the E in the absence of the other has no association by themselves with the phenotype. Interestingly, such interactions happen when the carriers of the genetic variant act against their genetic tendencies. An interesting paper published in Nature Metabolism this month reports a similar flavour of GxE interaction for a gene that is popular among the population and evolutionary geneticists.

LCT

Many of you might be familiar with the genetics of lactase persistence, a monogenic trait determined almost completely by a single genetic variant in LCT in Europeans that encodes the lactase enzyme. The variant strongly drives the behaviour of milk consumption. Individuals with the variant can produce lactase as adults and so commonly consume milk while those without the variant rarely do as they cannot produce lactase as adults. The Nature Metabolism paper by Luo et al. reports an interesting GxE interaction of LCT where they found that individuals without the lactase persistence variant who drink milk (violating their genetic tendencies) are at decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. The authors argue that in the absence of lactase in the gut, the lactose from the milk is available for the gut microbiota to consume, which increases certain beneficial species (like the ones in the probiotics) resulting in a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. However, many in the field speculate that the protective effect could be simply due to the effect of lower body weight that could be caused by lactose intolerance. Either way, the discovery of the GxE interaction alone is itself very interesting and adds a new chapter to the long-evolving story of LCT and lactase persistence.

ALDH2

I’d also like to highlight another paper published last month in Science Advances that I enjoyed reading. In the paper, the authors have performed a genome-wide GxG interaction analysis of the East-Asian specific ALDH2 missense variant rs671 and report several interesting GxG interactions, one of which, is the interaction of rs671 (in the gene ALDH2 encoding the enzyme that clears the acetaldehyde) with a variant in the gene ADH1B encoding the enzyme that produces the acetaldehyde (alcohol dehydrogenase). It’s a biologically interpretable interaction effect that has been long hypothesized but only now scientists have managed to demonstrate it empirically.

GxE and GxG interactions are interesting topic areas where most of the discoveries are yet to unfold, and almost all of them will be likely based on GWAS loci that we have known and heard stories about for a long time. New GxE and GxG discoveries will drop now and then in the coming months (and years) only to remind us that stories of those GWAS loci haven’t ended yet and there are many more chapters left to be written.

Sensational stories

If you refresh your memories about the major research findings of the year 2022, you might remember multiple sclerosis (MS) making the headlines at the beginning of 2022. MS took the spotlight with the publication of an extraordinary piece of epidemiological research in Science on January 2022. Analyzing more than 20 years of health data of millions of US military conscripts, Harvard researchers demonstrated a causal association between Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection and subsequent MS risk, confirming the long-hypothesized role of EBV infection in the MS aetiology.

Last year, the spotlight for the most sensational research finding moved from MS to Alzheimer’s disease after a preprint reported a “causal” association between shingles vaccination and protection from Alzheimer’s disease (and other dementias) using a natural randomization experiment. The authors analyzed vaccination and health data of individuals who were born in Wales a week before or after Sep 2, 1993, a date that was chosen by the government to determine eligibility for getting shingles vaccine. The random nature of the choice of the date made it a perfect instrument to mimic a randomized controlled trial where those born before and after the date represent randomized groups receiving or not receiving shingles vaccination. The authors found that those who received the vaccination were at significantly lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease, hence establishing a causality between the vaccination and the disease outcome. The Twitter post by the last author Pascal Geldsetzer from Stanford University went viral.

The year 2024 has just begun but already both MS and Alzheimer’s have been parading on the research headlines. Two sensational research papers came out last month, putting both MS and Alzheimer’s disease in the spotlight once again.

Multiple sclerosis

A series of ancient DNA research papers came out in Nature in early January. In one of the papers, a team of researchers from institutions across the globe report that they may have found clues in the ancient genomes from thousands of years ago that explain why MS is so common in northern parts of Europe. The authors argue that the origin of many of the genetic variants that increase the MS risk in current-day humans is tied to the arrival of Steppe pastoralists in Europe some 5000 years ago who brought with them not just the culture of animal herding but also the genetic risk for MS.

The MS risk variants that Steppes brought with them to Northern Europe might likely have already been under positive selection driven by some beneficial effects the variants conferred for survival. MS is an autoimmune condition and the strongest MS risk variant that correlates the most with the Steppe ancestry of present-day Europeans is a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) variant in chromosome 6. Hence, the authors speculate that the beneficial effect that drove these variants to high frequency in Steppes and later in Northern European settlers who admixed with Steppe is some sort of immune defence against animal-borne infections that they might have been exposed to due to the cultural practice of animal herding.

One major insight from the MS ancient DNA paper is the realization of the importance of culture and migration in human evolution. When we talk about natural selection, we often imagine the selection being tied to a specific geographical location where some environmental factor like harsh weather or an endemic infection drove beneficial genetic variants to a higher frequency. The paper reminds us that identifying signals of positive selection in humans living in certain parts of the world might not always necessarily indicate that the selection happened in the same region. It could be very well possible that the selection happened somewhere else and the selected variants and the environment that drove the selection were both brought to the region through human migration as was the case with MS.

Alzheimer’s disease

A few days ago, a fascinating paper came out in Nature Medicine where the authors report their encounters with what they believe to be the world’s first cases of Alzheimer’s disease caused by cadaver-to-human transmission. The fascinating part of the story is its background, which I have briefly summarized in a recent post.

The eight patients with early onset Alzheimer’s reported in the paper were members of an extremely unfortunate cohort who received 40 years ago a growth hormone injection prepared from pituitary glands dissected from cadavers for the treatment of short stature. This treatment was part of a nationwide health program in the UK between 1976 and 1985 during which nearly 30,000 children were dosed. Then the program was permanently shutdown following reports of deaths caused by Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) transmitted to a subset of the recipients through a batch of cadaver-derived growth hormone (CGH) vials contaminated with prion proteins from the infected brain.

It was long speculated that Alzheimer’s disease with amyloid protein aggregation at its core of pathogenesis might be transmissible from one human to another through infectious amyloid protein particles, just like prion diseases. However, except for the experimental evidence from the animal models, no human evidence has surfaced until now.

Two turning points in the 40-year-old story of CGH treatment have led to the current findings. One was when scientists found evidence of amyloid beta pathology in the postmortem brains of people who died of CJD from CGH treatment (published in Nature in 2015) and the other was when they found evidence of amyloid beta protein contamination in the CGH vials, eerily, from the same batch as the ones in whom previously scientists found evidence of amyloid pathology in the postmortem brains (reported in Nature in 2018).

Given the overwhelming pieces of evidence linking Alzheimer’s risk to CGH treatment, scientists knew long back that it’s just a matter of time before someone somewhere in the UK shows up with Alzheimer’s symptoms and a history of CGH treatment during childhood. And exactly as they predicted, they did.

Between 2017 and 2022, the neurologists at the UK’s National Prion Clinic (NPC) encountered eight patients with clinical presentations suggestive of Alzheimer’s and a history of CGH treatment during childhood. Remarkably, the medical records of four of these patients revealed that the CGH injections they received were from the same batch as the ones that the scientists reported in 2018 were contaminated with amyloid beta proteins and experimentally proved that the CGH they contained was capable of causing Alzheimer’s like pathology when injected into the mouse brains.

Despite the compelling story, Alzheimer’s in these patients might have occurred due to reasons unrelated to their childhood growth hormone treatment. However, given the overwhelming pieces of evidence, it is hard to not believe the speculation of Alzheimer’s being transmissible from human to human under extraordinary circumstances.

A GWAS with profound molecular insights

Speaking of natural selection, while on one side scientists study selection using old, common variants born several generations ago, spanning thousands of years (and so is common in the population), on the other side, scientists study selection using young, rare variants born a few generations ago. Scientists, particularly those in the drug target discovery field, are interested in an important characteristic of a gene: how tolerant is the gene to loss of function mutations, which informs whether the gene is under purifying selection. Genes that play a critical role in reproduction and development, as you can guess, will be under strong selection as any deleterious mutations in them will have little chance of getting passed through future generations.

Large-scale sequencing data help us to calculate the mutation constraint of a gene by comparing the number of rare deleterious variants in a gene observed in a healthy population to the number expected given the various characteristics of the gene. However, the current scale of sequencing databases is suitable only to estimate selection against heterozygous variants, but not homozygous variants as that would require extremely large data. But there are certain groups of genes called recessive genes that cause human diseases only when completely lost but not partially lost. So, you’d expect heterozygous mutations in such genes to occur commonly in the population but not homozygous mutations.

Last year, deCODE scientists published a paper in Nature Communications where they systemically searched for genes that are constrained for homozygous mutations but not heterozygous mutations and found many. They further showed such homozygous mutations cause recessive diseases that kill individuals at an early age or sometimes in utero. The deCODE scientists have a special interest in studying the processes that govern the birth and death of genetic variations both at the population level and at the molecular level.

Many of the landmark discoveries related to de novo mutations were made by deCODE scientists as, you know, they have genetic data for almost 80%1 half of the Icelandic population spanning multiple generations. In 2019, they published a paper in Science where they performed genetic association for an extremely fascinating set of traits related to chromosomal meiotic crossovers (estimated using multigenerational whole-generation sequencing data), the fundamental process that gives rise to new mutations generation after generation. One of the genes they discovered was SYCE2 which encodes a component of a protein complex that glues the homologous chromosomes together during meiosis and helps them exchange genetic materials. They found that a splice variant in SYCE2 results in an increased recombination rate and as a result, the number of de novo mutations in the offspring.

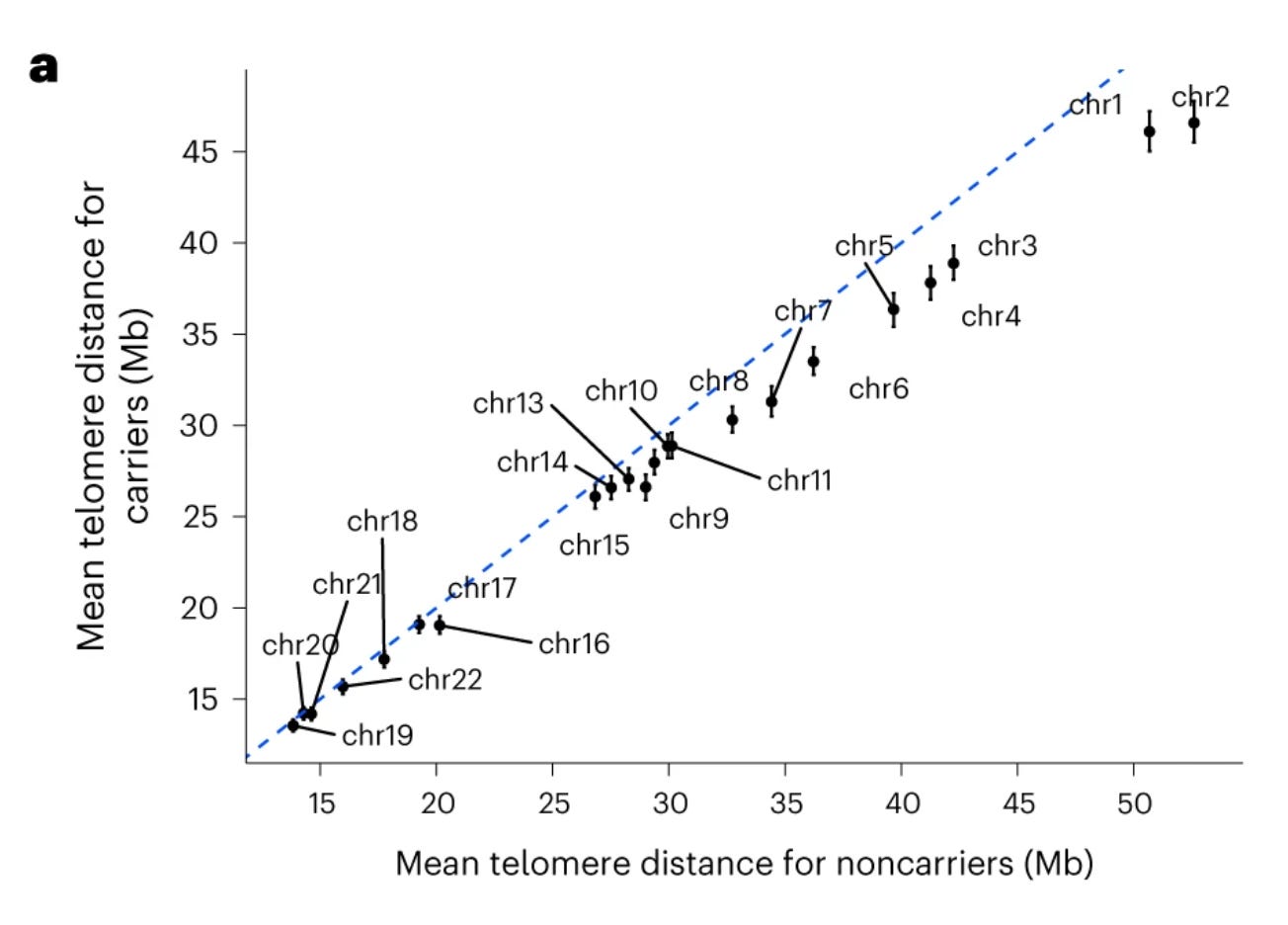

In a paper published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology last month, the deCODE scientists continue the SYCE2 story that they started telling in 2019. Studying the genetics of pregnancy loss through a GWAS in ~115,000 women, the authors found one strong signal in chromosome 6 where the top variant is a common missense variant in SYCE2, shedding light on their earlier findings on the association of SYCE2 with the increased rate of recombination. Using this opportunity, they revisited their 2019 data and found strong associations between the SYCE2 missense variant and many crossover phenotypes, of which my favourite is the distance between the crossover site and the telomere.

You see, telomeres are extremely complex and delicate regions and it’s bad to have crossovers in their proximity as that will increase the chances of large structural mutations resulting in chromosomal loss (aneuploidy) in the gametes, which is a strong risk factor for pregnancy loss. The figure above shows how close were crossover sites to the telomeres in the chromosomes in individuals carrying the SYCE2 missense variant compared to non-carriers. Such a deep insight coming right out of a GWAS signal is amazing and that is why I love almost every genetics paper that comes from deCODE genetics.

Genetic Discovery in Southeast Asians

In 1981, the Centers For Disease Control (CDC) published an article in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) about an alarming rise in the number of sudden deaths among Southeast Asian refugees. Almost all the deaths, the CDC investigators found, happened when the individuals were asleep, and based on the witnesses’ reports, all the deaths were sudden, happening minutes after the first sign of struggle. There were no apparent health issues shared among the deceased and all appeared to have been healthy before they went to sleep on the night of their death.

The researchers couldn’t pinpoint a common cause for the reported deaths based on the autopsy or the toxicology reports of the deceased. The only consistent autopsy findings were acute cardiac failure without any underlying disease. “The abruptness of the deaths reported here is compatible with a cardiac dysrhythmia, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear”, the CDC investigators wrote in the report. They soon learned that similar types of sudden deaths during sleep were commonly observed in the home countries of these refugees, known for generations in their respective native communities. In Northeastern Thailand, the condition was known by the name Lai Tai (“died during sleep”); in the Philippines, Bangungut (“moaning and dying during sleep”); in Japan, Pokkuri (“sudden unexpected death at night”). The CDC decided to call it sudden unexplained death syndrome (SUDS).

The 1981 CDC report stirred a great interest among epidemiologists, pathologists, cardiologists and researchers to investigate the cause of SUDS. One among those who were intrigued by the report were Gumpanart Veerakul, Apichai Khongphatthanayothin and Koonlawee Nademanee, cardiologist researchers at the Bangkok Hospital, Thailand, who would later go on to study and publish papers on SUDS for the next 30 years (including the one that I am highlighting here).

In 1997, Nademanee and colleagues published in the journal Circulation what would become a seminal paper in the literature on SUDS. Studying 27 Thai men with a history of cardiac arrest during sleep caused by ventricular fibrillation, Nademanee et al. found that ECG abnormalities of the SUDS patients were identical to that of a recently found novel cardiac syndrome, which would later bear the name of its discoverers from the Brugada family—Pedro Brugada and Joseph Brugada.

Despite that Brugada syndrome was extraordinarily common in Southeast Asia, the gene for Brugada syndrome was discovered not based on South-East Asians but on Europeans. Just studying a handful of patients, researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine got their hands on the breakthrough finding of the gene responsible for Brugada syndrome—SCN5A that encodes the cardiac sodium channel—published in Nature in 1998.

Later it became apparent that even if the first genetic studies were performed in Southeast Asians, the odds of discovering SCN5A based on just eight cases would have been low, as it turned out the genetics of Brugada syndrome in Southeast Asia is more complex than in Europe. Only less than 6% of the cases in Southeast Asia were caused by pathogenic variants in SCN5A which is in contrast to Europe where nearly 20% of the cases were caused by a known pathogenic variant in SCN5A.

The striking contrast in the genetic diagnoses between Europeans and Southeast Asians motivated researchers to search for genetic variants, particularly outside the coding region of SCN5A, that might explain the high prevalence of the condition in Southeast Asians. Those efforts recently led to the discovery of a noncoding intronic regulatory variant in SCN5A as one of the major genetic causes of Brugada syndrome, explaining 1 in every 25 cases in Southeast Asia. The discovery was made by Thailand researchers along with their long-term collaborators from Amsterdam.

The SCN5A intronic variant is probably the first disease-causing rare noncoding variant with a large effect size discovered based on a population-based study in a non-European ancestry and hence, well deserves the spotlight. The work was preprinted in medRxiv last December.

That is all for now. Hopefully, there’ll be more such roundups this year.

—Veera

I wonder since when I started believing deCODE sequenced 80% of the population. Referring to my old threads, I’ve always written ~45%. Anyway, sorry for the error. Based on deCODE’s statement on their website—we have gathered genotypic and medical data from more than 160,000 volunteer participants, comprising well over half of the adult population—and on their recent paper—About 155,000, or close to half of the Icelandic population of 340,000, have participated in an ongoing nationwide research program at deCODE Genetics—it is a little less than 50%.